year

post

Oct 13, 2011

2011 10 13 Material Interfaces Part Ii

First, just quickly: I'm quoted in Monday's Boston Globe article about the Awesome Foundation. I've sung their praises here before, of course.

And I'm now through the first section of work in my course on Crafting Material Interfaces at the MIT Media Lab. (Here's the first post about this class.) We're documenting our work all through; you can click through from the home page of the class web site to "all postings" and see the notes and images from various experiments and fact-finding there.

We looked at conductors in this first section—and we were all assigned various groups of conductive materials that expand far beyond the traditional metals and such. Instead, we looked at conductive polymers, inks, adhesives, and nanotubes(!). My group looked at conductive elastomers—basically stretchy rubbers and rubber/plastic-like substances. Like other polymers, elastomers are usually used for the insulating properties, so making them conductive means some fancy work to reconfigure their basic properties. The result, though, is that you get conductive materials that can essentially be molded and extruded to almost any imaginable shape (shapes that can be pricey or limited with metals).

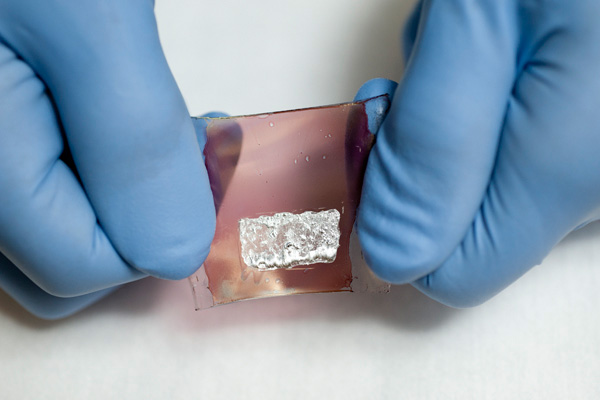

The best part of this research is digging into materials research, understanding intrinsic properties, and then—best of all—getting familiar with the advanced and weird and stunning range of materials out there, and their applications. (See conductive foam, metal rubber, stretch-sensing rubber, and this electronic skin, a project out of Stanford:

The foundation for the artificial skin is a flexible organic transistor made with flexible polymers and carbon-based materials that can be stretched up to almost one-third of its size without compromising any of the mechanisms or losing power. The cells maintain a wavy microstructure that extends like an accordion when stretched, and a liquid metal electrode conforms to the surface of the device in both its relaxed and stretched states. (via Inhabitat, see link below)

And the skin is super sensitive—it registers the brush of a butterfly, seen in this video:

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RYFVtH3hiC0&w=560&h=315]

To finish our experimenting with conductors, we each had to work with a material, or create an entire design using nontraditional conductive parts along the way. I felted some knitted wool with silver thread sewn throughout. Here's before felting:

And here's after:

The thread was a little worse for the wear, but the conductivity suffered only slightly. There are about a million kinds of electronic wearables you could make out of this kind of thing at Kobakant and Instructables.

[vimeo http://www.vimeo.com/29996043 w=500&h=889]

Crafting Elasticity from Daekwon Park on Vimeo.