year

post

Mar 6, 2011

2011 03 06 Whats Wrong With Prosthetics Porn Part Ii

Part I of this essay is here.

How can technologies demonstrate an outward posture? I mean, how might they extend their forms and also their functions, beyond a single user? Couldn't they both resolve and reveal, pose more questions than answers?

In the first part of this essay, I included examples of adaptive wear and prosthetics that dazzle with their efficiency and beauty. But those tools have created a superficial salve for our fragile bodies and our mysteriously variable minds. They're great for the gizmo and gadget blogs, for the cool factor. But why not ask our tools to do more—more than get a makeover, I mean?

[Randy Mora's El Futuro de la Educación]

I've been tracking a number of blogs and other writing in architecture and urban planning, and in those fields, I read a similarly restless critique of our persistent object fixations. Even while these fields have largely abandoned the self-conscious, grand-gesture confidence of Modernist utopian thinkers, they remain dominated by an emphasis on structures—newly-imagined, newly-built artifacts that aspire to offer some social critique but rely too heavily on material design.

The research group Spatial Agency has a useful database of architects and art where social practices and systems are much more at the foreground. Citing Bruno LaTour's call for an architecture that shifts attention from itself as "a matter of fact to a matter of concern," Spatial Agency collects the work of practitioners for whom "a spatial problem doesn't necessarily call for a building."

It won't surprise you that I think artists have a lot to offer here. I want to see more technologies and interventions function in this open-ended way, where a solution, spatial or otherwise, may be proposed, but the project's very nature also visualizes the problem(s) at hand, left open for study. I'm thinking of interventions that form their own questions and leave those questions intact. Like Michael Rakowitz's paraSITE:

Rakowitz collaborated with people in need of housing to create customized shelters like these—ingeniously re-routing the wasted heat exhaust from the vents on city buildings.

[image credit: M. Rakowitz.]

Or REBAR's parking space—I've blogged about this project here before:

It's modular, temporary public leisure space, created by re-purposing dedicated car-parking spots.

These projects realize something useful without a false sense of solution, where the materials are only as important as the ephemerality of the situation.

In the same way, adaptive technologies needn't always be things: extensions, replacements, enhancements. And when they do employ objects, adaptive tech will be its strongest if it resists neatly closing the story line that goes between before and after, between the broken body and electronic super powers, between the once-down-trodden and dependent, and the now-overcoming disabled hero. If we want to shed the scientism that keeps telling us this story—ever more progress, in a neat and marching forward fashion, versions 3.0, 4.0, 5.0—we need more technologies that keep the questions open, hold opposing ideas in tension. (See also: art!)

A built environment, a city that accommodates—and indeed demonstrates—physical or cognitive interdependence doesn't only call for limbs and ramps. We need wholly-spectacular impracticalities, and artistic research and collaboration, and public interactive art, and we need the most durable accessibility equipment we can design.

The generative wandering-about that can happen between the fictional and the practical affirms the need for both. The prosthetic wonders that are all the rage: These speculations cast an eye beyond the limits of our imagination, but at their best, they could critically loop back into questions about accessibility at large.

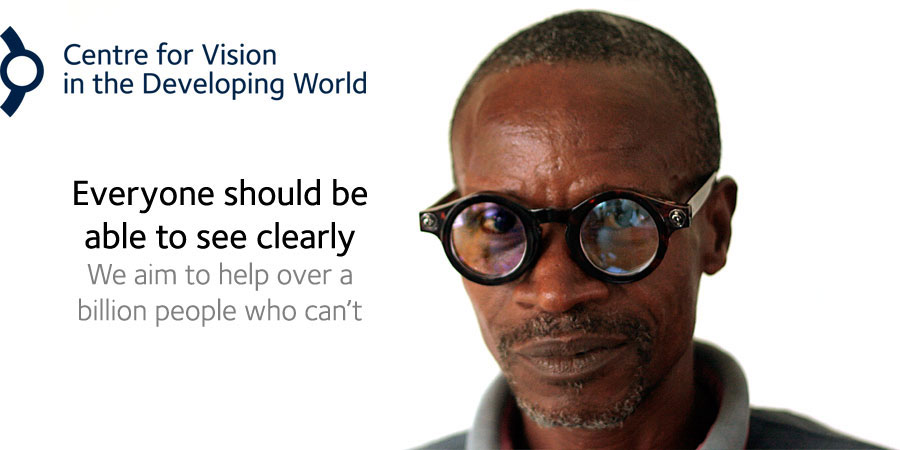

There's got to be room for both the Eyeborg and adjustable-focus, low-cost eyewear:

Moreover, we might take the long view in order to get the short view more clearly in focus. This has long been said of science fiction in literature—that our ideas about the future are really an index of our attitudes in the present. I'm interested in futurism in prosthetics as an inquiry and spectacle, and I also want to make projects that help us harness our technologies for a more inclusive world.

Still with me? So here's one way I'd like to explore cities with interdependence in mind, with a not-new technology, creatively re-deployed: Tandem cycling.

Lots of cities are touting their bike-sharing programs these days. Mexico City has its own Eco-Bici program; the city also created a tandem-sharing program, where one rider is sighted and the other is blind. A partnership of Bicitekas, Muévete por tu Ciudad, and Contacto Braille programs, the tandem rides take place on Sundays, on designated closed streets:

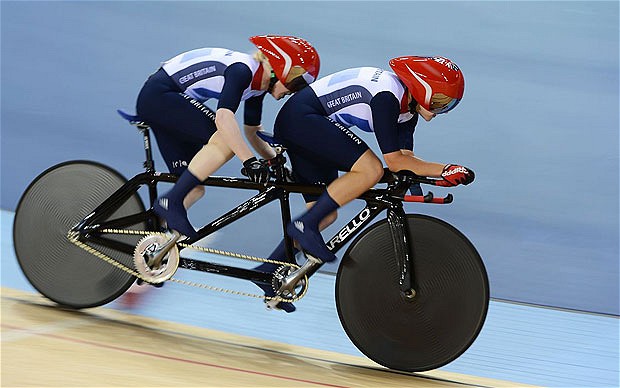

Of course, tandems with one sighted and one non-sighted rider aren't new. Paralympic teams have been riding competitively for a long time—the front rider is called the Captain (who is sighted), the back rider the Stoker (who is blind).

The art of tandem-ing is pretty nuanced. You have to know your partner well to communicate with subtlety; you have to maximize the physics of the situation to really harness the power of both people. It's not an automatic doubling of the human power. And the captain/stoker terminology is just interesting—it's like interdependence made visible, like a sustainable working system where there's no clear power dynamic:

[image credit here.]

So I've been thinking a lot about the metaphors present in tandems, and I've been interested in speculative bicycle technologies, like Rory Hyde and Scott Mitchell's Spoke-O-Dometer:

The Spoke-O-Dometer "broadcasts the current speed and cumulative distance of a cyclist from the wheel of the bike. The device calculates this information in real time via a small computer, and uses "˜persistence of vision' technology—LED's that flash in a specific sequence as the wheel spins—to produce the display. Exposing this information creates the potential for new social interactions between cyclists and the public."

This technology is still being developed, and Rory and Scott say it's not truly readable yet. But I love its potential as a social tool for altering the shared space of the city street, and with tandems, even moreso.

So here's my question, one for which I'll thank you for your help with the promised drawings (and collaborator credit if it goes somewhere):

What could happen with a bunch of tandem bikes as a large-scale interactive public art work, employing some data gathering along the way? The riders wouldn't necessarily have to be blind and sighted teams—just the interdependence is what's at issue here, in addition to other possibilities. How could you network the bikes, or program them in a social fashion, or attach something that would map routes, or otherwise make it collaborative?

Anything's fair game here—flights of fancy, seemingly unrelated thoughts, vague suggestions most welcome. I realize there are lots of practical issues that would have to be worked out, but we're in the development stage: What could make a bunch of tandem bikes a visible, critical, social experience in a city?