year

post

Feb 20, 2011

2011 02 20 Whats Wrong With Prosthetics Porn Part I

When I started Abler, I was excited about all the new prosthetic appendages beginning to make their way through design sites. And I remain so—excited about, intrigued by them. I've been collecting these images, sent on by friends and colleagues, and I've been glad to see much more attention to both practical and creative re-visioning of artificial limbs.

But all the whiz-bang sex appeal of these objects is worth looking at more critically. With this new set of essays, I'll try to capture some of the excitement and energy of this trend and engage some of its detractors. And then I want to propose that we can ask for much more from our tools than we do now—and run by you an idea I have. I'll need your feedback!

But let's begin at the beginning, with this:

Kaylene Kau's prosthetic arm boasts a "flexible tentacle design."

An example of the totally-custom limbs available from Bespoke Innovations. They're made with a user's overall "look" in mind.

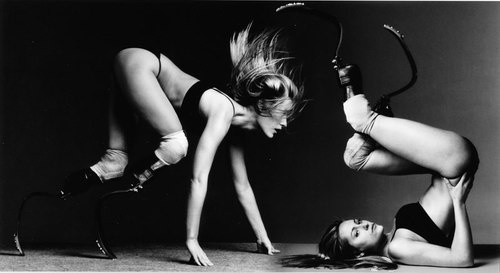

And here's Aimee Mullins, an athlete, double amputee and famous owner of multiple pairs of high-fashion, custom-designed legs:

Mullins is ever making the rounds at TED and other venues, rightly calling for augmentations like these legs that show off their beauty and variation, shrugging off the old stigma around this kind of abnormalcy. And now, every week it seems, another object appears for future use by the disabled, slick and colorful, sci-fi fantasies intact.

And it's great—except—I think we partly love these objects because they give the illusion that we'll just strap them on when our bodies fade. A neat exchange of old for new, and we're off toward the post-human without missing a beat.

Craig Wallace, a wheelchair-user writing for the Australian Broadcasting Company's Ramp Up blog, complains that we've got a kind of fetish thing going for this gadgetry, a lot of which ends up as "technological cul-de-sacs," when the designers and engineers who purportedly want to "give hope to the disabled" would be better occupied elsewhere:

"[The media has] this idea that we're all sitting around waiting for a miraculous piece of [tech] that will re-assemble us people with disabilities into impersonations of the real article. [It's] a 21st century incarnation of faith healing, with the same premise—that we're all waiting to be cured and sprinkled with holy water, only this time swimming with nano particles."

[Cyberdyne lab's HAL (Hybrid Assisted Limb) increases your arm and leg strength as much as tenfold(!).]

Wallace wants our energies to go instead toward near-future applications that increase daily accessibility. His suggestions include "a light wheelchair that won't shatter into pieces at airports, has reliable brakes and doesn't cost the equivalent of the plane it's travelling on," or "a bank teller machine that people who are vision-impaired or short-statured can use."

Hard to argue with that, at least in political terms. The recent appearance of this universal subtitler for video is a great example of such practical technology. Access is at its heart, and it's ultimately simple.

There are further problems to consider. I've already expressed my wariness about the rhetoric surrounding these technologies: that when we consume these victory-over-disability images uncritically, we skirt our uglier collective repulsion about dependence. It's akin to the continued resistance we have to talking about aging. Only about a quarter of adults in the U.S. have had serious conversations about end-of-life decisions, and it's generally of the crisis kind—what happens if we die suddenly. We imagine that we'll be here one day in a basically static, able version of ourselves, and not the next. The prospect of a longer, slower period of weakness—or any protracted change in our capacities—is just too threatening to anticipate.

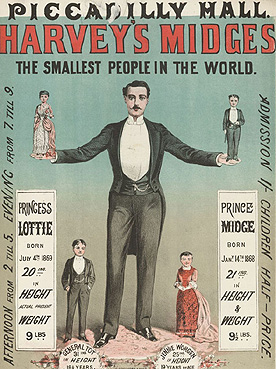

And, as Matthew Battles points out, sporting bells-and-whistles-body-part-gizmos may run the risk of inviting a kind of "freak show" fascination that drew attention to abnormal bodies in the 19th century, dividing "us" from "them," however unintentionally.

[From the British Library's Bodies of Knowledge collection.]

Which brings me to consider a question someone asked me after a lecture I gave last year: Is it preferable to design adaptive devices that are elegantly designed to be camouflaged (think hearing-aid jewelry), or beautiful and conspicuous, like the legs above? And, with Wallace in mind, should we ethically aim more design research toward near-future applications, rather than wildly speculative gear that may never see the light of day?

Well—yes. To quote Maile Meloy: Both ways is the only way I want it.

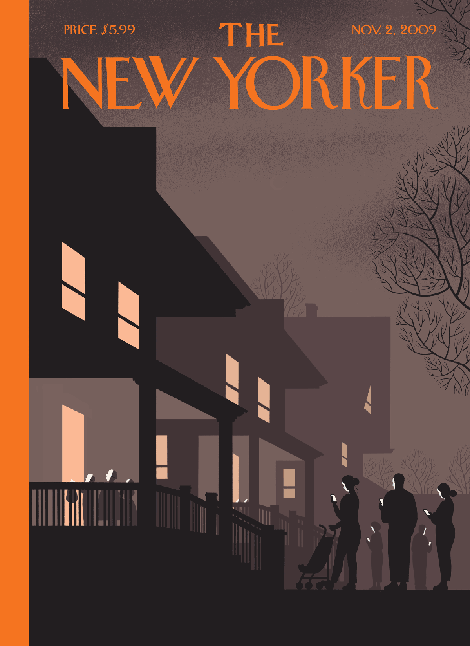

I think our energy can go in all these directions, provided we're reflective enough. I've already affirmed the inherent value in playful experimentation. But the bigger challenge is to make extensive machinery that is truly extensive, truly outward in its posture. I think design matters crucially to these questions, because design for disability has the opportunity to critique the weakness of all personal technologies: its tendency to hermetically seal its user from engaging, interdependently, on the public street.

[Attention to this image via Greg Smith at Serial Consign.]

To put it another way: That ever-fancier leg—and I'm a fan of those legs!—gives much-needed independence to amputees who use them. This is enormous and worth celebrating. But blithely claiming the "end of disability" with those gadgets alone doesn't really help us figure out how to live with dependence, and dependents, in our greater cultural ecology. In our normative on-the-street experience, we have to keep creating a culture that can tolerate and dignify needs, that can keep affording accommodations. These are subtler moves.

And living with dependence may not really be about objects—or about shiny new objects, anyway. Next, I'll explore ideas in urbanism and architecture, and I'll draw some connections to what adaptive technologies, and adaptive practices, can add to the future of the built environment.

[Chen Yugang's Face-to-Face tandem bike.]

More to come! [You can read Part II here.]