year

post

May 17, 2010

2010 05 17 Adaptation Part I How The Eames Chair Came From Leg Splints And Why Disability Studies Isnt Just Identity Politics

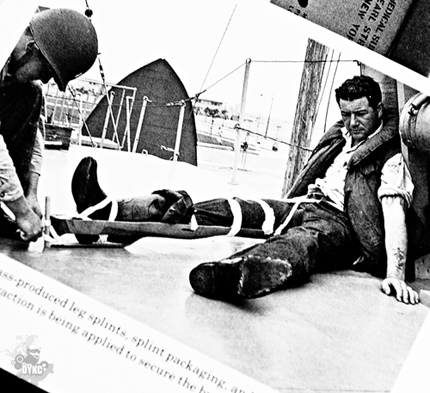

In 1941, the husband-and-wife design team, Charles and Ray Eames, were commissioned by the US Navy to design a lightweight splint for wounded soldiers to get them out of the field more securely. Metal splints of that period weren't secure enough to hold the leg still, causing unnecessary death from gangrene or shock, blood loss, and so on.

The Eameses had been working on techniques to mold and bend plywood, and they were able to come up with this splint design—conforming to the body without a lot of extra joints and parts. The wood design became a secure, lightweight, nest-able solution, and they produced more than 150,000 such splints for the Navy.*

Over the next decade, the Eameses would go on to refine their wood-molding process to create both sculpture and functional design pieces, most notably these celebrated chairs:

Graham Pullin, in his book, Design Meets Disability, cites this story as an example of a seemingly specialized design problem—a practical aid for disabled soldiers—that inspired a whole aesthetic in modernist furnishings. The chairs that launched a thousand imitators, and a new ethos of simple, organic lines in household objects.

It's easy to assume that the innovation would more often happen in reverse: that a generalized design solution would "trickle down" to the narrow confines of adaptive technology. But this example, as Pullin points out, suggests that disability concerns may be an overlooked area of aesthetic inspiration, able to point to creative breakthroughs that have wide relevance and impact.

More than that, I think it demonstrates why we should all pay more attention to disability matters.

It's easy to imagine that "disability studies" is just one more category of identity that's purely for political advocacy, interesting only to those directly affected by issues of accessiblity, accommodation, or special rights. But if we pay greater critical/theoretical attention, we'll understand that "disabledness" is a far more slippery designation than the other ways we have of organizing ourselves—along the lines of race, gender, ethnicity, and the rest. And while these latter categories have also been shown to be much less stable than once thought, disability is another matter altogether. Let me explore two big reasons why disability concerns are everyone's concerns.

First, we make a false divide when we make a we/them: either able-minded, able-bodied, or disabled. After all, how we define, think about, and treat those who currently have marked disabilities is how we ourselves may well be perceived if and when we become less abled than we are now: by age, degeneration, or some sudden change in our physical or mental capacities. We will all, over the course of our lives, traffic between times of relative independence and dependence. So the questions we ask, the technologies we invent, and how they broadcast a message about their users—weakness and strength, agency and passivity—are important ones. And they're not just questions for scientists and policy-makers; they're aesthetic questions too.

Second, in the West at least, we maintain a near-obsession with averages and statistical norms about our bodies, personalities, and capacities that we take for granted. But this way of measuring ourselves is historically very recent, and worth reconsidering.

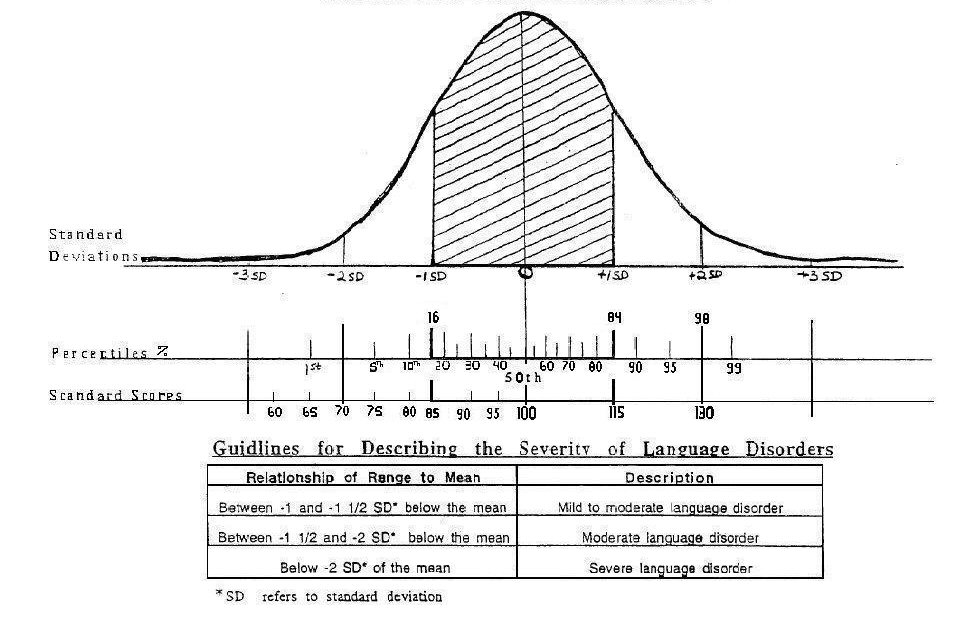

Disability studies scholar Lennard Davis writes that

"before the nineteenth century in Western culture, the concept of the "˜ideal' was the regnant paradigm in relation to all bodies, so all bodies were less than ideal. The introduction of the concept of normality, however, created an imperative to be normal, as the eugenics movement proved by enshrining the bell curve (also known as the "normal curve") as the umbrella under whose demanding peak we should all stand. With the introduction of the bell curve came the notion of "˜abnormal' bodies. And the rest is history"" [italics mine]

Bending Over Backwards: Disability, Dismodernism, and other Difficult Positions

You all know the bell curve, of course.

It's the source of all our talk about how we measure up, relative to others. In case you doubt the obsession, I invite you to witness the conversation among parents of young children: It's all percentiles, and milestones, and being "ahead of the curve" with respect to each month of a child's development. Exceptional normal-ness is what they prize above all else, and it's this measurement that can reassure anxious caregivers, despite little correlation between these measures and a lifetime of wellness, healthy relationships, or sustaining work.

Again, Davis reminds us that this is a recent set of cultural ideas, so naturalized that these standards have a way of "enforcing normalcy." Measurable normalcy is the current ideal, even as we know, increasingly, that all the facts about us—our neurological profiles, our temperament, our long-term achievements—are marked by singularity, variability, and idiosyncracy.

"It's too easy to say, 'We're all disabled,'" Davis writes. But it's a challenge to interrupt our cultural assumptions in powerful, creative ways—and alter how we think about our own dependence, independence, and that of others.

So how do artists engage these myths about what's normal, and make more visible and expansive the concept of a fluid abled/disabled identity?

That's in Part II, coming next. If you want, you can subscribe to my RSS feed or get email notifications for future posts—on the home page.

*You can read more about the splints in Neuhart, Neuhart, and Eames, Eames Design: The Work of the Office of Charles and Ray Eames.

splint and chair images from this Flickr set and the Herman Miller site.