Facebook's experimentation with its users' feeds was a big story this summer. And last week, tech writer Tim Carmody pointed to the curiously less-scandalous news that online dating site OKCupid has done the same thing with its data.

Early last week, as a guest writer for Kottke, Carmody considered the differences between the two platforms and the forms those interventions took, and why the press so far has varied widely about the news. In the later part of the week, he returned to the discussion with a detailed analysis of both cases, getting beyond both simple outrage and a shoulder-shrugging, you're-the-product cynicism.

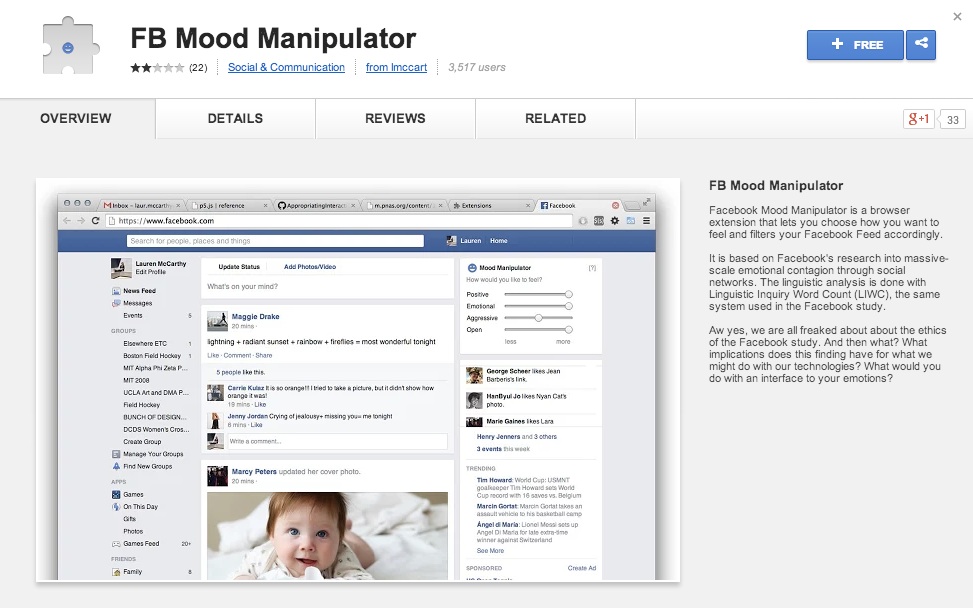

I've long loved Lauren McCarthy's work, so I took note of her Mood Manipulator Facebook plug-in—a small set of tweaks for tuning the mood of your feed all by yourself. The manipulator makes a small widget in the upper right corner of a user's Facebook screen, asking her to indicate emotional wishes with sliders, to amplify or inhibit certain kinds of moods. Users can dial up or dial down their wishes for "positive," "emotional," "aggressive," or "open" inflections in their feeds.

I emailed with Lauren a bit, asking her to talk about making this work, and what she found interesting about the study and its reception in the news:

"Everyone was talking about the ethics of the study, and few people were talking about the actual implications of the findings. Of course, the paper didn't contain a ton of surprising results, but just to be thinking about how the technologies we build affect our emotional state is important. This sort of research happens in academia, but to see it enacted in a large-scale, actual system we interact with made the results affecting for me.

"I was inspired to make the mood manipulator to explore that question of what the findings could mean. Facebook is unlikely to give us this kind of explicit control, but thinking more broadly about the systems we are building—what if we could have an interface for our emotions? What if it went beyond just Facebook, but filtered all the content of our lives? Would we want it? How would we use it? Is it wrong to turn down the volume on your friends' depressing feelings on the days when you just really need a good mood? Is it wrong to want to be happy and to use technology to augment your ability to do this? And maybe our emotions aren't as simple as unhappy <--> happy. How do you begin thinking about what you really want to feel?"

McCarthy also mentioned the ways this project (and others of hers) mimics the slick-and-easy language of personal tech ads:

"My framing it as 'take back control' was sort of tongue in cheek. Are you reclaiming control by willingly giving it over to an algorithm, even one you set the targets for? I saw tweets describing the extension as 'a tool for empowerment.' Maybe."

As Carmody pointed out, one of the most interesting facts in this whole story is how many people who use Facebook (something like 60%) don't realize their feeds are manipulated at all. That's another register of Lauren's plug-in—simply showing the plasticity at work in such a monolithic platform, and suggesting that it might be changed by others than Facebook's own designers:

"I also just wanted to make something playful, that perhaps inspired a little reflection for those that used it. And to show that the black boxes we imagine FB and other technologies to be, are penetrable, hackable. LIWC (the system used in the FB study and the extension) is an open dictionary that is quite straightforward to work with, and to use for whatever purpose you decide."

See more of Lauren McCarthy's Mood Manipulator.